Though they frequently share the same vocabulary, their definitions come from different dictionaries. Shaefferian thought utter rejects NAR.

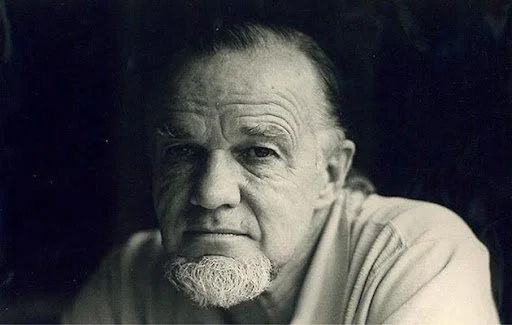

In recent years, various movements within evangelicalism have appealed to “worldview,” “cultural engagement,” and “Christian influence” language popularized by Francis A. Schaeffer. Among these is the movement commonly known as the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR). While NAR proponents often echo Schaeffer’s concern for cultural decline and Christian responsibility, the theological framework of NAR fundamentally contradicts Schaeffer’s epistemology, doctrine of revelation, and understanding of the church. As a result, appeals to Schaeffer in defense of NAR theology represent a serious misappropriation of his work and intent.

At the center of Schaeffer’s entire apologetic and worldview project was the conviction that Christianity is objectively true because God has spoken. Against both secular humanism and religious mysticism, Schaeffer insisted that biblical Christianity rests upon propositional, verbal revelation given by an infinite-personal God. He stated plainly, “The true Christian position is that the infinite-personal God has spoken to man in propositional, verbalized form.”¹ For Schaeffer, Scripture was not a record of subjective religious experience but God’s public, authoritative communication to humanity. He warned that once Christianity abandons objective revelation, it inevitably collapses into subjectivism, insisting that “once you cross the line from reason to non-reason, you are no longer talking about truth.”² This commitment to objective revelation placed Schaeffer firmly within the Reformation principle of sola Scriptura, even as he engaged philosophy, culture, politics, and art.

One of Schaeffer’s most enduring analytical contributions was his critique of the modern “upper-story / lower-story” divide. In this framework, truth, reason, and factual knowledge are confined to the lower story, while religious belief is relegated to a non-rational upper story of experience. Schaeffer identified this move as fatal to Christianity, observing that “modern man lives in the upper story of experience, separated from the lower story of reason and fact.”³ When religious authority is grounded in personal experience—visions, impressions, or prophetic utterances—rather than Scripture, Christianity loses its claim to truth and becomes indistinguishable from mysticism. This critique applies directly to NAR theology. Despite verbal affirmations of biblical authority, NAR teaching regularly elevates prophetic revelation, apostolic insight, and subjective spiritual impressions as authoritative guidance for the church. Even when described as “non-canonical,” such revelations function authoritatively in practice, placing them squarely within the upper-story epistemology Schaeffer warned against.

Schaeffer was explicit that Christianity is grounded in what God has already revealed, not in ongoing revelatory authority. He emphasized that “the Bible is not a collection of religious experiences, but a body of truth communicated by God,”⁴ and further insisted that “Christianity is not a series of personal experiences, however real, but truth concerning what God has done in history.”⁵ NAR’s insistence on present-day apostles and prophets who receive strategic revelation for the church represents a functional denial of the sufficiency of Scripture. This is not a minor doctrinal disagreement but a direct challenge to the foundation of Christian authority as Schaeffer understood it.

A defining mark of Schaeffer’s worldview thinking was his insistence on antithesis—the sharp distinction between biblical Christianity and all competing systems of thought. He wrote, “There is a line of antithesis between Christianity and all non-Christian thought.”⁶ Christianity, for Schaeffer, could not coexist with alternative authority structures without surrendering its truth claims. Any movement that introduces parallel sources of authority stands outside the bounds of biblical Christianity. NAR’s apostolic hierarchies, prophetic networks, and alignment structures introduce precisely such competing authorities. These systems inevitably relativize Scripture by subjecting the church to leaders who claim special revelation or divine mandate beyond the written Word.

Although Schaeffer strongly believed Christians must engage culture, he rejected triumphalist or utopian expectations of cultural transformation prior to the return of Christ. He warned that “the Christian is not called to total withdrawal, nor to the illusion of a perfect society before Christ returns,”⁷ and cautioned further that “there are no utopias this side of heaven.”⁸ NAR’s dominionist impulses, often expressed through kingdom-now theology or the Seven Mountain Mandate, conflict with Schaeffer’s sober eschatology. Where NAR anticipates societal conquest through spiritual authority and apostolic strategy, Schaeffer anticipated faithful witness amid cultural decline, grounded in truth rather than power.

Finally, Schaeffer located the credibility of Christianity not in supernatural power displays or institutional dominance, but in truth expressed through love and obedience to Christ. He wrote, “The church is to show forth the holiness of God in the midst of the world—not by power, but by love.”⁹ For Schaeffer, the church’s calling was cruciform rather than triumphalist, marked by faithfulness, suffering, and clear truth in a fallen world. The NAR emphasis on authority, power, and spiritual governance stands in tension with this vision of Christian witness shaped by the cross.

In conclusion, while the New Apostolic Reformation may borrow Francis Schaeffer’s language of worldview and cultural engagement, it rejects the theological foundations upon which his thought rested. Schaeffer’s unwavering commitment to Scripture alone, propositional revelation, antithesis, and a non-triumphalist eschatology places him in fundamental opposition to NAR theology. This church therefore affirms that NAR teaching is incompatible with historic Reformed Baptist doctrine and represents the very form of experiential mysticism and authority-shifting that Francis Schaeffer devoted his life to warning the church against.

Footnotes

Francis A. Schaeffer, Escape from Reason (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1968), chap. 4.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Francis A. Schaeffer, He Is There and He Is Not Silent (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House, 1972), chap. 3.

Ibid.

Francis A. Schaeffer, The God Who Is There (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1968), chap. 1.

Francis A. Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live? (Old Tappan, NJ: Revell, 1976), chap. 13.

Ibid.

Francis A. Schaeffer, The Mark of the Christian (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1970), 19.